from Commons-Wikipedia

Searching for an overarching world view based on Liberty at a time when there is much discussion about Liberty & Freedom, and/or lack thereof.

Definitions of Liberty (from Oxford Languages Dictionary):

1. Liberty, the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views; the power or scope to act as one pleases.

2. Freedom, independence, free rein, freeness, license, self-determination; free will, latitude, option, choice; volition, non-compulsion, non-coercion, non-confinement; leeway, margin, scope, elbow room.

3. Independence, freedom, autonomy, sovereignty, self-government, self-rule, self-determination, home rule; civil liberties, civil rights, human rights

Each decision and action should be viewed and weighed relative to the production or strengthening of Liberty. Those decisions and actions may, at their start, reduce a sense of Liberty in the short term in order to produce greater overall Liberty. Examples of this type of trade-off are as follows:

The concept of war. While war represents violence and constraint- even subjugation, it may be used to create greater Liberty by freeing a greater amount of people from tyranny. A war may be fought to liberate people, but it should never be fought to repress them. Because war is an extreme act, it must be the last act taken after all other methods of movements towards Liberty have been undertaken. If a war is not providing more Liberty and/or is never-ending, war should be ended.

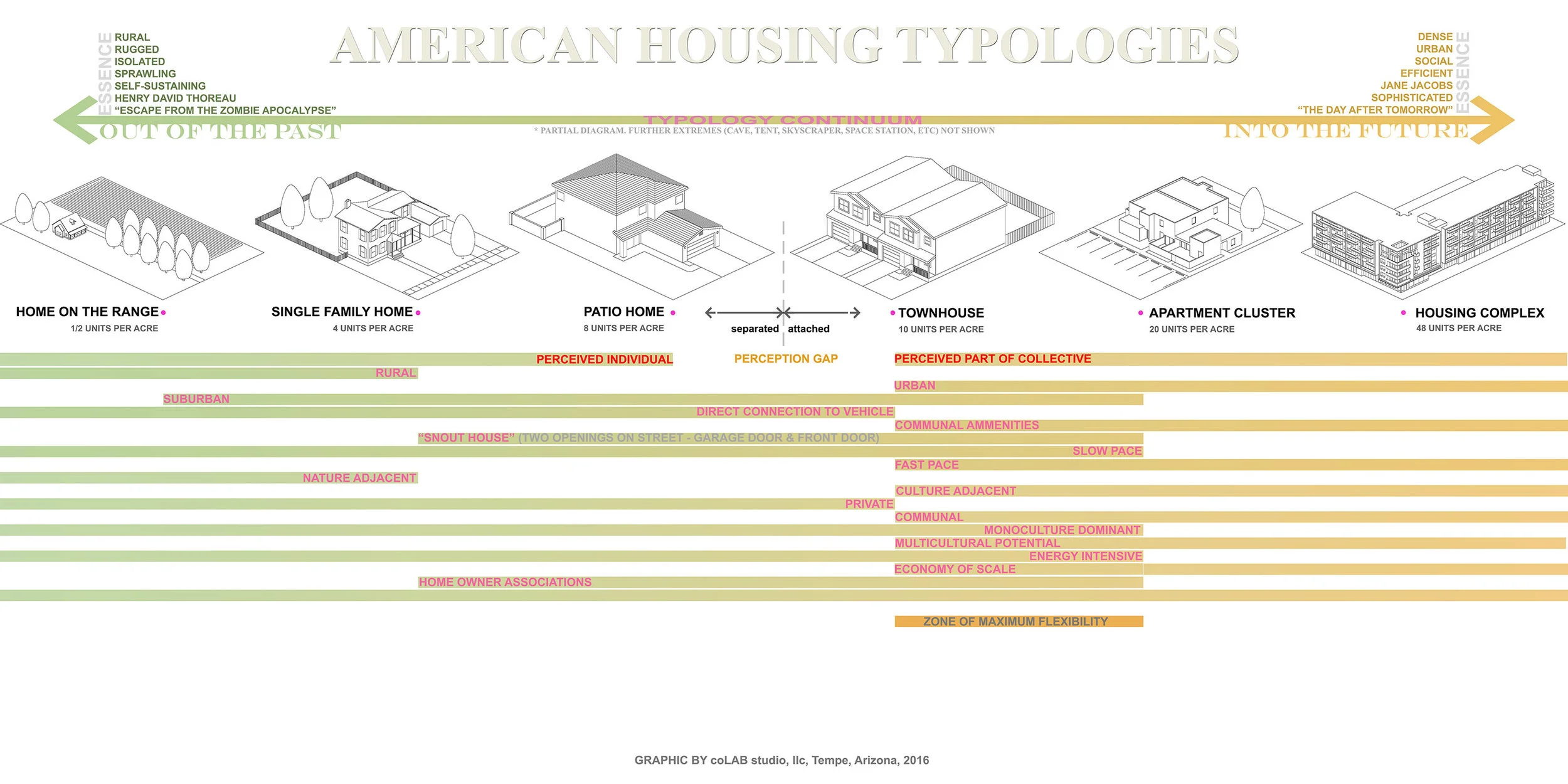

The concept of marriage. While the joining of two people is, in one sense, the opposite of freedom and independence, the act of marriage is designed to create a bond between people such that their comprehensive Liberty is greater than the sum of their individual Liberty. This may also be accomplished by creating a small community of two (or more) that work together towards common goals that provide the best opportunities for life, liberty, and happiness. This may require a reduction of Liberty for one or more participants at times, but should always be working towards an ultimate increase of Liberty for all involved. If it fails to produce greater Liberty for too long a period, the marriage or communal arrangement should be ended.

The concept of employment. While the act of employment is a form of subjugation for an individual, it is often undertaken to provide for greater Liberty for that individual in the long-term. The employment may provide sufficient funds and free time for the individual to enjoy their lives in a greater capacity than without the employment. This may not always be the case immediately upon employment, but needs to eventually fulfill the need of sufficient or increasing Liberty in order to be of value to the individual. If employment does not provide greater immediate or eventual liberty, the arrangement should be ended.

Government, likewise, should constantly be working to increase Liberty, though may produce complicated situations. Think about the “social contract” citizens of the United States have with the police. We allow the police to hinder one’s Liberty, at times, in order to keep the greater peace.

There are many different views of what Liberty is. Laws may produce varying degrees of Liberty for different people. In order to figure out how to govern and produce laws that provide the greatest amount of Liberty for the maximum amount of people, there must be a great deal of discussion on weighing the options. And those discussions must constantly revolve around the idea of Liberty for the governed. This includes the notion that “all men are created equal,” with an understanding of “men” as all human beings (not the pejorative use of the word, but a much wider understanding of humans.)

But what if we expand our understanding of the notions of “all ‘men’ are created equal” and “liberty and justice for all,” the latter being a part of the United States Pledge of Allegiance. What would it take to create true Liberty around the world for all species? For instance, there is a patchwork of justice for animals in the United States. Some protect typical pets (dogs and cats), while some (like Maine) have laws that protect “every living, sentient creature not a human being.”

Though if we consider the world as an interconnected network of species and environments that are symbiotically joined, rather than consideration of a single animal, shouldn’t we create laws to protect everything? After all, if the animals cannot survive without places to inhabit and food to eat- which is provided by healthy ecosystems- then damaging the environment would equal cruelty to animals and therefore be against the law.

To look at this yet another and more historical way, the very old idea of The Commons, where natural resources belong to everyone to partake in. This concept should allow any and all of us to “live off the land.” The problem is when there are too many people utilizing The Commons using up all its resources, which then leaves most people with less than they need. And it begs the question: How can we have Liberty for ourselves, as humans, if we do not live in a healthy environment that provides us enough nourishment to live a free life?

Much of the ideas of Liberty stem from the basic human desire for self-determination. Yet the earliest humans imaginable gathered in communities, requiring each individual to make space for other individuals. Anthropologists surmise the goal was a greater chance for individual survival for each member of the community. Without the community, life expectancy for each individual would be significantly shorter. A shorter life equals less liberty. Giving up some self-determination can be beneficial overall in the long term, both for the individual and the community.

What appears to have changed is the concept and availability of individual wealth provided by modern law and liberal economic policies for the past 200 years. Those securing longevity through wealth (for themselves and their families) need not work to the benefit of others because they need little or nothing from “others.” This idea of stratification is seductive, as it suggests higher levels self-determination and less subjugation- for anyone with the gumption to work for their success. Though reality is far more complicated and unequal.

Not everyone that gives up on community needs such wealth. In our modern age, some Americans attempt to live lives of great personal freedom while willing to give up wealth and a potential safety net that comes with being a part of a community. Some surely feel it is worth it even if they struggle with health issues and may ultimately die prematurely. In many ways I feel these individuals should be allowed to forego the safety net.

Yet, the less people that participate, the less of a safety net there is. In addition, those that have no safety net are nearly always utilizing tax dollars to pay for huge medical bills at the end of their lives, as the majority will not live with the cruelty of letting them suffer and die without care. Some do not want to pay into a social system at all, while others live and die by the existence of a safety net. This makes governing difficult for the masses.

It is even more complicated when taking into consideration every species on the planet as potential equals with humans when it comes to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” There is no wide-spread understanding on how much to prioritize plant and animal species relative to humans. A millennia’s-old idea that humans are more important than animals certainly tips the scale towards people. The “Great Chain of Being” even has a graphic depicting a specific hierarchy placing humans atop, larger animals above lower ones, plants below animals, and minerals last. Even with recent new scientific understanding of how our human bodies (and even brains) are in a constant symbiosis with invisibly small creatures, who sometimes guide us, we have a difficult time seeing them as life-partners. And equally difficult to understand large but out-of-sight animals, for instance the Grey Wolf, as important to our survival. But they are. Every part of every ecosystem is important for the survival of our species. If we destroy them, and the environment, we remove a great deal of our own personal liberties due to decreases in food, finances, and lifespan.

We know we are in the midst of a mass extinction of species on the planet, some referring to it as the Anthropocene Extinction (meaning human-caused.) The current great reduction of pollinators (ex: bees) as a serious threat to humanity’s survival is only one part of the complex picture in this mass extinction. There are other threats to humans from this issue as well, and they may be enough to wipe out humanity within a century. In the United States alone there are reports that 40% of animals and ecosystems are at risk of extinction. If that happens, many predict there will be a global food supply collapse. Some of the collapse will be brought on by wars that do nothing but lower Liberty for everyone involved. (The example of Russia’s war on Ukraine is an example of a completely unnecessarily brutal assault affecting so much of the world.) Deliberate industrial destruction and war will hasten a human demise.

Thus, one may argue providing more liberty to non-humans will ultimately produce more long-term liberty to ourselves in the form of individual and species immortality. (I think of Roy Batty asking his creator for “more life.” Given the sudden recent rise of artificial intelligence, this feels even more poignant.) Species longevity may be ultimately the most important way to think about Liberty. Without your life you have zero liberty—you simply do not exist. We should consider what we know will extend our own species existence, both for the self and our species, as a community. A healthy planet not only accomplishes human longevity, but does so in relative comfort.

Arguments are made against taking care of the planet because it would erode personal liberties such as the availability of convenient plastics or flying around the world to the finest beaches. Yet we can also demonstrate and are aware of lots of ways to help the environment. Some may consider each of those suggestions to be a burden eroding their personal Liberty. I can understand that. But there are always trade-offs in life, and undertakings that are burdensome in order to achieve something desired are often necessary. In this case, taking care of the greater environment is a trade-off that is ultimately in pursuit of your own life, descendants, and those of others.

Going back to our earliest ancestors’ decision to form communities, to give up some self-determination in order to stay alive—was that not the right choice? I would submit we are in that situation again, only we now understand the “wider community” we need to team up with is much more diverse (global, environmental) and we are largely in control of the relationship. It is up to us.

The real goal should be to not just live in harmony with nature, like a good neighbor, but to become a smarter and more passionate participant of nature. And while I am not 100% sure what that really means or looks like, I imagine it would include searching for all the ways we can encourage positive human interactions with nature to allow the environment to thrive and evolve while providing greater health for all species.

One simple example (by itself only a small start) would be to help bees grow their populations, thereby increase our own food production in the process, by providing bee habitats all over the world. A million tiny habitats could make a big impact, and can be provided around our homes and cities.

But the larger solution will require very large and complicated inclusive solutions. We will need to utilize all of our accumulated knowledge and compassion for each other and our environment. And we need to, simultaneously, hold onto our belief in Liberty. The task will be a lot harder without it, or may miss the target entirely.